An electoral process that is flawed will ultimately produce misfits as leaders and a nation perpetually doomed.

At sixty-five, Nigeria ought to stand as a towering beacon of democratic maturity and good governance in Africa. Instead, her democratic project remains trapped in a cycle of betrayal, where electoral infidelity – the deliberate subversion of the people’s will has become both symptom and cause of her arrested development. The promise of independence in 1960 was that of a nation destined for greatness: a federation that would marry its vast human and natural resources with accountable leadership to secure liberty and prosperity. What has unfolded is a persistent sabotage of that promise, with elections, the heart of democracy, reduced to rituals of manipulation and deceit.

This issue is not merely electoral malpractice but a profound erosion of the social contract. The ballot box, meant to confer sovereignty upon the people, has become an instrument of elite consolidation, undermining legitimacy, corroding institutions and destroying the moral authority of governance. The protagonists are the ruling elites who orchestrate fraud, aided by compromised electoral commissions, pliant judiciaries, and security agencies weaponised against the electorate. The antagonists are ordinary citizens whose will is thwarted, alongside fragments of civil society and opposition voices that refuse to capitulate.

Historical roots of electoral infidelity

This malady has deep roots. The elections of 1959, which ushered Nigeria into independence, were marred by allegations of rigging and census manipulations, setting a precedent. The disputed 1964 federal elections and the 1965 Western Region crisis showed how the ballot could trigger instability. As Chief Obafemi Awolowo observed, “A rigged election is worse than armed robbery.” His words proved prophetic: the First Republic’s collapse in 1966 stemmed from eroded legitimacy through electoral fraud. The Second Republic fared no better. The 1979 elections saw the Supreme Court stretch constitutional interpretation to validate Shehu Shagari’s victory in Awolowo v. Shagari. By 1983, the National Party of Nigeria perfected electoral brigandage, declaring results with impunity. As Bola Ige quipped, “It was not an election; it was a selection.” The resulting legitimacy crisis invited another military coup. The annulment of the June 12, 1993, election, Nigeria’s freest and fairest, by military fiat, and the fraudulent 2007 polls, described by international observers as “the worst they had ever seen,” cemented a pattern: the ballot manipulated to preserve incumbency rather than reflect popular will.

Mechanisms of manipulation

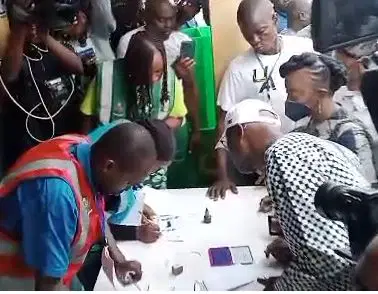

Electoral infidelity takes many forms: crude violence like ballot snatching and voter intimidation by thugs or security forces; subtler manipulations of voters’ registers, constituency boundaries, and collation processes; and the widespread purchase of votes with cash or inducements, turning elections into auctions. Worst of all, courts often serve as final rigging centers, awarding victories on technicalities rather than merit. The Electoral Act of 2022 introduced safeguards like the Bimodal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS) and the INEC Result Viewing Portal (IReV), but their inconsistent deployment in 2023, marked by delayed result uploads in states like Lagos and Rivers and allegations of manual tampering, revealed persistent elite sabotage. I foresee similar challenges in 2027 unless systemic reforms are prioritized. The judiciary’s role in post-election adjudication has deepened perceptions of “cash-and-carry” justice.

Why it persists

The persistence of electoral infidelity lies in the self-preservation of Nigeria’s ruling class – a ruling class that appears clueless over the decades and has foisted a regime of underdevelopment on the nation. Control of state power guarantees access to oil rents, contracts, and patronage, making elections existential battles to capture the treasury. Weak institutions, monetised politics and the absence of ideological parties entrench this pathology. In a poverty-stricken society, vote commodification is inevitable. As Chinua Achebe lamented, “The trouble with Nigeria is simply and squarely a failure of leadership.” That failure is sustained by electoral infidelity, which thrives nationwide. In rural areas, poverty makes voters vulnerable to inducements; in urban centers, collation manipulation and judicial compromise dominate.

The cost of electoral infidelity

The consequences are profound. Politically, it produces governments devoid of legitimacy, answerable to patrons rather than citizens. Economically, it stifles development, as leaders lack the incentive to deliver public goods. Socially, it breeds cynicism and alienation, reflected in voter turnout plummeting from 69% in 1999 to 27% in 2023. This disillusionment fuels a broader malaise: democracy without opposition. Nigeria increasingly mirrors states where opposition is hollowed out through inducement or intimidation. Opposition members defect to the ruling party for survival, creating a political monoculture, parliaments that rubber-stamp executive whims, elections without meaningful alternatives and governance without accountability. The “Japa” phenomenon, mass emigration of young Nigerians, reflects both economic despair and political hopelessness.

History offers cautionary parallels. Weimar Germany’s institutional fragility enabled the Nazis to eliminate opposition, leading to dictatorship. Mexico’s Institutional Revolutionary Party maintained power for seven decades through systemic fraud, reducing elections to rituals. Venezuela, and Hungary under Orbán, have mastered procedural democracy devoid of substance, while Zimbabwe’s ZANU-PF shows how manipulated elections breed apathy, economic collapse and emigration. Nigeria risks a similar trajectory. If voting changes nothing, citizens disengage, leaving space for extremism or radical alternatives like populist demagogues or violent uprisings. As Abraham Lincoln warned, “Elections belong to the people. If they decide to turn their back on the fire and burn their behinds, then they will just have to sit on their blisters.” Nigerians are sitting on blisters not of their making. Remember, the 1966 and 1983 military coups that overthrew civilian governments gave as an excuse, electoral and election manipulations . Nigeria does not want a military coup. But, again, look at the trajectory in neighbouring countries.

PATHWAYS TO REDEMPTION

Cosmetic reforms will not suffice. Redemption requires restoring institutional sanctity. The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) must be truly independent, with autonomous funding and appointment processes insulated from executive control. Ghana’s transparent collation process, where results are tallied at polling units and publicly verified in real time, offers a model Nigeria could adapt to eliminate manipulation. The judiciary must be cleansed of perceptions of bias, as Lord Denning noted: “Justice must be rooted in confidence, and confidence is destroyed when right-minded people go away thinking: ‘the judge was biased.’” Electoral offenders, no matter how highly placed, must face swift prosecution. Political financing reforms must curb the monetisation of politics, while civic education, especially targeting youth through digital platforms, can empower citizens to resist inducements.

Comparative lessons abound: Mexico’s 1990s revival through independent electoral oversight; South Korea’s democratic reforms after authoritarianism; and Ghana’s steady electoral improvements show change is possible with institutional will and civic pressure. Nigeria’s political culture must shift toward accountability, pluralism, and fidelity to the rule of law. The Constitution declares that sovereignty belongs to the people; subverting their will is constitutional infidelity, a breach of the supreme law. The maxim, salus populi suprema lex, the welfare of the people is the supreme law, must guide reform.

As Nigeria approaches 2027, the warning signs are clear. If the electoral umpire undermines the people’s will, if opposition is further emasculated, if judicial compromises persist, democracy may not survive unscathed.

Electoral infidelity imperils the Republic’s survival. Yet, at sixty-five, Nigeria can redeem her democratic promise through courage, civic, institutional and moral. Citizens must demand integrity, institutions must enforce it and leaders must embody it. Without this, democracy remains a façade, the vote worthless, and the promise betrayed.

Nigeria can fix Nigeria by confronting its greatest affliction: the betrayal of the ballot. Until then, electoral infidelity will remain the albatross around the nation’s neck, condemning her to unfulfilled promise and deferred greatness.

Olufemi Aduwo is the President & Permanent Representative, Centre for Convention on Democratic Integrity (CCDI) to the ECOSOC/United Nations

olufemi.aduwo@ccdiltd.org | www.ccdiltd.org | CCDI is a non-profit registered in Nigeria and incorporated in the State of Maryland, USA. It has held the United Nations ECOSOC Consultative Status since 2017.

VANGUARD.