As Nigeria moves deeper into its annual Lassa fever season, an unsettling pattern has emerged: the virus is increasingly infecting the very people tasked with containing it.

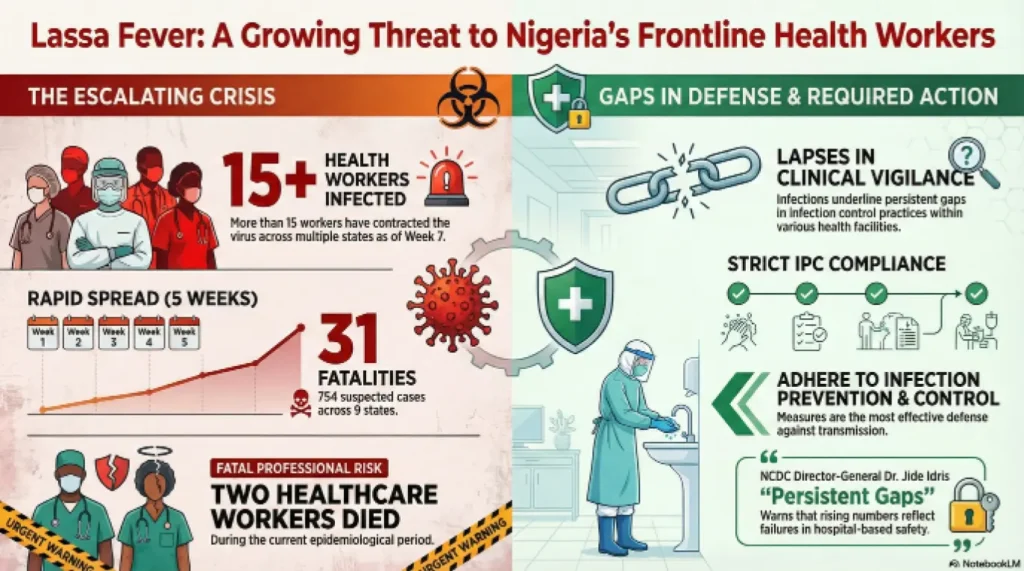

According to the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), more than 15 healthcare workers across multiple states had contracted Lassa fever as of Epidemiological Week Seven, with two deaths recorded. In the first five weeks of the year alone, 31 people died from the disease, while over 754 suspected cases were reported across 33 local government areas in nine states.

The data reflect not only the seasonal resurgence of the virus but also persistent vulnerabilities within health facilities, where frontline workers remain exposed.

In an advisory issued in Abuja amid rising case numbers, the NCDC Director-General, Dr Jide Idris, warned that strict compliance with Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) measures remains the most effective defence against hospital-based transmission.

He said the infections among healthcare personnel underscore lingering gaps in clinical vigilance and infection control practices in some facilities.

Strict adherence to IPC practices, early detection, and coordinated state-level action will save lives and prevent further transmission,” Idris said, describing the loss of trained medical personnel as deeply concerning and detrimental to outbreak response capacity.

The NCDC has urged state governments and health facilities to establish functional isolation units, maintain designated treatment centres where feasible, and ensure clear referral pathways for suspected cases.

Understanding Lassa fever

Lassa fever is an acute viral haemorrhagic illness caused by the Lassa virus, a member of the arenavirus family, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The disease is zoonotic, meaning it is transmitted from animals to humans, primarily through exposure to food or household items contaminated by the urine or faeces of infected Mastomys rats, commonly known as the African multimammate rat.

The illness is endemic in Nigeria and several West African countries, including Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Sierra Leone and Togo. Experts believe it likely exists in other countries in the region where surveillance systems are weaker.

While rodent-to-human transmission remains the dominant route, person-to-person infection can occur, particularly in healthcare settings where adequate infection prevention measures are absent, the WHO has warned.

Since the major outbreak in 2016, Nigeria has witnessed recurring seasonal spikes, typically between November and April. High-burden states this year include Ondo, Edo, Bauchi, Taraba, Ebonyi and Benue, with several local government areas identified as hotspots.

Healthcare workers are considered the first line of defence during such outbreaks. Their exposure not only reduces available manpower but also heightens the risk of secondary transmission if cases are not identified and isolated promptly.

Voices from the frontline

For many health workers, the risk is no longer abstract.

A nurse at a federal medical centre in one of the affected states, who requested anonymity because she was not authorised to speak publicly, described the anxiety that now accompanies routine patient care.

“Every fever case now makes you pause. You ask yourself, is this malaria, typhoid, or something more? Sometimes the protective equipment is not enough, and you still have to attend to the patient,” she said.

A resident doctor, Godwin Ekweke, echoed similar concerns.

“The challenge is that early symptoms of Lassa fever mimic common illnesses. By the time suspicion is raised, several staff members may already have had contact with the patient,” Ekweke said.

Clinicians note that exposure risks extend beyond doctors and nurses. Cleaners, laboratory technicians, ward attendants and administrative personnel may also be vulnerable when infection control protocols are inconsistently applied.

“It’s not just about the doctors. Everyone in the facility must be protected, from the cleaner to the consultant,” said Ajasa Kehinde, managing director of God Is Able Hospital in Kubwa, Abuja.

Why infections are rising among health workers

Public health experts attribute the rising infections to a combination of seasonal, clinical and systemic factors.

A senior doctor at Kubwa General Hospital in Abuja, who asked not to be named, said the early symptoms of Lassa fever, including fever, weakness and headache, are non-specific and easily mistaken for malaria or other febrile illnesses common in Nigeria.

In many primary and secondary healthcare facilities, patients are initially treated for malaria or other common febrile illnesses. This delay in suspecting Lassa fever can expose multiple staff members before isolation protocols are activated,” he said.

He noted that IPC guidelines are well documented nationally, but implementation varies significantly between facilities.

“In some cases, lapses in hand hygiene, improper use of personal protective equipment and inadequate waste disposal increase occupational risk. Standard precautions must be applied to every patient, not just suspected Lassa cases. You cannot wait for confirmation before protecting yourself,” he added.

Dr Hammed Alausa, another physician, pointed to supply chain challenges. Although national agencies distribute protective materials during outbreaks, temporary shortages at the facility level sometimes occur.

“Even brief stock-outs of gloves, gowns or disinfectants can increase vulnerability,” Alausa said, adding that procedures involving blood or bodily fluids, such as inserting intravenous lines, cleaning wounds or handling laboratory samples, carry heightened risk if protective measures are compromised.

A physician, Chukwudi Ifeanyi, highlighted another factor: delayed self-reporting among healthcare workers who develop symptoms.

Stigma, professional pride or fear of isolation may contribute to late presentation. That increases the risk of complications and potential transmission,” Ifeanyi said.

Consequences of a compromised frontline

When healthcare workers fall ill, the consequences extend far beyond individual cases, public health specialists have warned.

First, staffing shortages intensify pressure on already overstretched facilities. During peak Lassa fever season, treatment centres often operate at or beyond capacity. Losing trained personnel can compromise patient care and prolong waiting times.

Second, morale suffers. Fear of infection may discourage staff from volunteering for high-risk units, particularly in rural areas where health worker density is already low.

Third, public confidence can erode. If hospitals are perceived as unsafe, communities may delay seeking care, potentially worsening disease outcomes and fuelling further transmission.

“If health workers are not protected, the entire health system becomes fragile. Protecting them is not optional; it is strategic,” Alausa said.

These experts warn that safeguarding healthcare personnel must be viewed not merely as an occupational issue but as a central pillar of epidemic preparedness.

The way forward

Specialists outline both immediate and long-term interventions to curb infections among health workers.

They suggest regular, mandatory IPC training for all categories of facility staff, clinical and non-clinical, as essential. Simulation exercises and on-the-job mentorship, they believe, can reinforce correct practices. Similarly, strict adherence to hand hygiene remains fundamental. Alcohol-based hand rubs and functional handwashing stations must be readily accessible across facilities.

The experts also said facility-level stock monitoring systems can help prevent shortages. Transparent reporting of inventory gaps allows for rapid redistribution before supplies are exhausted. They also recommend decentralised buffer stocks during peak transmission periods.

Hospitals must implement robust triage systems to identify and isolate suspected Lassa fever cases at first contact. Dedicated isolation areas reduce exposure risk for other patients and staff. Clear referral pathways should be communicated to lower-level facilities to prevent unnecessary exposure.

Rapid laboratory confirmation is critical. Delays prolong uncertainty and increase exposure risk. Improved specimen transport systems and expanded laboratory capacity can significantly shorten turnaround times.

They also advised that healthcare workers need clear, stigma-free pathways to report symptoms or exposure and access testing and treatment promptly. Psychosocial support services can help address fear, burnout and anxiety.

Healthcare workers must feel safe reporting symptoms. Early treatment improves survival and protects colleagues,” Ifeanyi said.

DAILY TRUST.